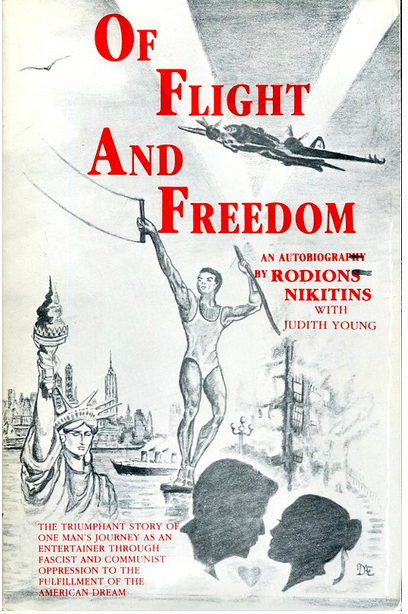

The Latvian-born circus performer Rodion Nikitins lived through WWII performing in different circuses and theatres in Latvia, Germany and Nazi-occupied Prague. In his autobiography Of Flight and Freedom from 1987, Nikitins confesses that his work as an entertainer gave him more opportunities and options during WWII than those available to his family members or friends in Latvia.

When the Soviets occupied Latvia in 1940, Nikitins was performing at the Latvian Circus Salamonski in Riga. The Soviets forced the circus to prepare a new programme every month. Nikitins remarked that obtaining new material to develop new acts was easier at the time due to the pressure to constantly create new shows. The Soviets insisted on the importance of performers to the civilian morale, and cir-cus performers kept working throughout Soviet occupation. At the same time, many Baltic States citizens simply disappeared.

On June 22, 1941, Nazi German troops began their invasion of Soviet Union territory. The German occupation of Latvia was completed by July 10, 1941. The new occupiers instructed the circus to change the programme, but, like the Soviets before them, insisted that the circus continue its operations. The liminality of the war made Nikitins and his partner Koni take even more daring risks in their acrobatic act. After witnessing one of their spectacular and risky shows, a fully-uniformed member of the National Socialist party came on-stage and declared: “What a finale. As long as we have men like you, we cannot lose the war!”

As the German military position weakened, Nikitins feared he would be mobilised to fight against the Red Army. At this moment, Nikitins decided to use his entertainer status to flee to Germany. He also saved his brother by forging Leo’s name into his contract as an assistant. To further justify his brother’s presence on stage, he decided to create a comedy acrobatic act with him.

Nikitins presented his acts in Berlin, Magdeburg and Hamburg. During one terrible night of air strikes in Hamburg, the theatre where Nikitins was performing was struck. Nikitins was the last act of the programme, and he had left his wire standing on the newly reinforced stage. Miraculously, Nikitins’ wire was still standing untouched, but the theatre and all its walls had unravelled around it. Nikitins knew that he would have never been able to afford new wire material to replace his equipment.

After Allied air raids on German cities increased, Nikitins decided to perform in German-occupied Pra-gue. After the breown of the National Socialist Regime in spring 1945, Nikitins had to be moved into a school accommodation with other international entertainers under Czech supervision. While in his temporary lodging, Nikitins once offered a German prisoner of war a light for his cigarette. The in-cident looked bad in the eyes of the Czech guards and Nikitins was almoakdst executed for sympathising with the previous occupiers.

Soon after entering the American zone, Nikitins was able to find work entertaining American troops in Heidelberg and in other towns nearby. After realising that Latvia would not regain its independence af-ter WWII, he decided to emigrate to the United States. Eventually, Nikitins became a naturalized American citizen, but he had to realign his career by establishing schools for gymnastics and dance. His perseverance, versatility and courage helped him to survive and rebuild his life after the war.

Author: Pauliina Räsänen

Source: Nikitins, Rodion: Of Flight and Freedom. Hand Voltage Publications, Seattle, WA, USA 1987.

Great article Pauliina,

Pauliina

This is very well written, succinct and compelling piece causing me to reflect on the performer’s life as well as stretching my own vocabulary (“liminality”). If this is a sample of what you hope to write in your history of Circus I think you are on to something extraordinary.

Richard